Academia as homebase for societal innovations

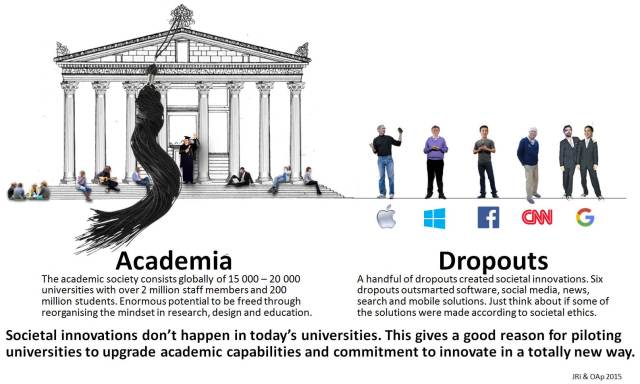

Image. The natural homebase and context for societal innovation is the academia, the university. The university is an ideal setup for large, systemic and groundbreaking innovations. It has the latest knowledge from research, most motivated students to learn to understand, organise and plan the future according to scientific proofs. Still there is much to learn about dropouts and the outer world.

Image. The natural homebase and context for societal innovation is the academia, the university. The university is an ideal setup for large, systemic and groundbreaking innovations. It has the latest knowledge from research, most motivated students to learn to understand, organise and plan the future according to scientific proofs. Still there is much to learn about dropouts and the outer world.

The role of university in societal innovation, is there one?

The academic world is used to expect constant innovations and breakthroughs from such academic fields as medicine, biotechnology and informatics. But what about the humanities and social sciences? Nobody expects anything groundbreaking from a linguist or a political scientist – let alone an economist. Why social and political scientists can’t, are not allowed or are unable to innovate?

Where does the current societal innovation come from – is there any? Why aren’t work and employment, social security, education, health care, finance, (local) governance, plan and design of new cities targets of active innovation – they should be.

For the time being society is expected to develop and transform itself, but this merely thanks to technological inventions. If we allow this to happen, tomorrow’s society is being built technology first, not human first. Is this a desired direction? We are merely outsmarting ourselves with the obligation of everything to be so damn smart nowadays to get money or attention – projects, conferences, consumer goods – that we forget the basics. Societal change can be done without a chip or a tag on everything just for the sake of technology and the touted productivity gains expected from it.

Social and political fields of academic study and research are stuck in studying history and documenting some specific political and societal events and are thus merely seeking to record to later generations what happened and eventually pinpointing to the underlying generic structures behind various phenomena and behaviour. Explaining why and how something happened. Is that good enough? Is the role of social and political scientist confined to that of second mover. Meanwhile, accompanied with solid academic ethics, they should be the first movers.

Being a second mover is clearly not enough. Why would these academic fields have the luxury to just observe and document, at the best case react to some phenomena or event – academia obliges if journalists demand comment. It is of course good to be able to analyse and reason the surrounding world, know some history, but it is not enough. The graduates leaving social sciences faculty, having studied political sciences and economics, for example, merely have learned to understand and study the current structures of our societies, their institutions and modes of functioning. When they leave their respective universities they go and become part of the existing machinery –they do not seek to change anything and are incapable of creating new.

Meanwhile, what they should have learned instead (or in addition at least) is how to envision, plan and execute (at least pilot) something new on their field of study: new employment models, new theories and practices for (local) economy, new towns and structures for (local) government, for example.

The solution to the current lack of ‘human first’ innovations is this little change in the study program of those academic fields dealing with societal issues.

The social science and humanities faculties should immediately add to their study program planning, envisioning, understanding of structures, concrete doing and execution as an essential part of the curricula. For the time being these skills are mainly possessed by engineers, designers, architects and artists.

When we remove a little bit of history and researching from for example from the political science study program and add to the program future and the creation of new as new dimensions, societal innovation becomes a natural part of education.

Each student must be tested, instead of, or in addition to, his knowledge about political history, also in his capacity to create new – new cities, employment mechanisms, governance structures, economical theories and practices.

Are universities ready to innovate?

It seems that universities have been caught by the rhetoric of innovation at times of rather long lasting economic slowdown. But are universities able or ready to innovate? Why should they? Is innovation in their range of activities and part of their historic role? It seems that the fundamental debate about universities’ role in innovation is yet to take place.

In order to respond to the hype and fight for ever decreasing funding for education, many universities have recently simply changed their name into ‘Innovation universities’ or have done so after apparent ‘joining of forces’ between different higher education institutions. Like if linking institutions would make people more innovative. Those who think that by merely linking people (interdisciplinary), institutions and networks you create innovation, have never invented a thing themselves and don’t have a clue about the driving forces behind innovation.

Why weren’t university professors and researchers of communication, media or sociology able to predict the need for social media and did not answer to that need by developing a social media product/service that was ethical? We bet Google or Facebook would not be the omnipresent stalkers (for financial profit AND for pure joy of infringing one’s privacy) had they been developed by academia and its R&D and P&D ethics. But the academic world did not invent or develop them because of the mere observer role of a university. Professors are good in researching what already is and was before and documenting trends, not predicting the future, nor envisioning, planning or designing it.

However, a university professor is supposed to be the highest reference on his field of study, owing the largest up-to-date knowledge and understanding of his subject. This is certainly the case as to what comes to mastering a specific field’s historic development and current trends. But that’s not enough, if universities are asked to innovate. It is not enough to have a separate ‘study of the future’ or foresight department and think that something will eventually come out of there. Having made a tour to have an idea of what these foresight institute in various universities do – they merely build up a networks amongst themselves, yet again thinking that the networking is the key and merely hoping that a member of the network invents something.

From R&D to P&D and more

If a university, after a fundamental talk on its societal and scientific role, decides that it should indeed innovate, mere statement of the fact, participation in various networks of ‘excellence’, change of name into an innovation university or piling up faculties and schools to bring in “interdisciplinarity” are not enough.

A university needs to add some Planning and Design (P&D) next to its R&D. This is to say, research and development are not enough to innovate. The various academic fields of study need to incorporate into their programs of study P&D. That’s the vast horizontal capacity focused on the future and creating new that is missing in all academic fields of study, except from the fine arts and engineering. Only artists and engineers are taught to envision, plan, design and execute – to create. Why shouldn’t others?

The first university that creates, pilots and consolidates P&D into all of its academic teaching and thus gives everyone from a social scientists to a statistician the skill to plan and design societal change will be both in its own country as well as globally the first mover in the field of societal innovation.

You must be logged in to post a comment.